Мұзды бұрғылау тарихы - History of ice drilling

Ғылыми мұзды бұрғылау 1840 жылы басталды, қашан Луи Агасиз арқылы бұрғылауға тырысты Unteraargletscher ішінде Альпі. Айналмалы бұрғылар алғаш рет мұзды бұрғылау үшін 1890 ж.ж. қолданылды, ал жылытылатын бұрғылаумен термиялық бұрғылау 1940 жж. Қолданыла бастады. Мұзды корольдеу 1950 жылдары басталды, онжылдықтың аяғында Халықаралық геофизикалық жылы мұзды бұрғылау белсенділігін арттырды. 1966 жылы Гренландия мұз қабаты термиялық және электромеханикалық бұрғылаудың тіркесімін қолданып, 1388 м саңылауымен тау жыныстарына дейін бірінші рет еніп кетті. Келесі онжылдықтардағы ірі жобалар Гренландия мен Антарктиканың мұз қабаттарындағы терең тесіктерден ядролар әкелді.

Қолмен бұрғылау, ұсақ өзектерді алу үшін мұзды шнектерді пайдалану немесе абляциялық қазықтарды орнату үшін буды немесе ыстық суды пайдалану арқылы бұрғылау кең таралған.

Тарих

Агасиз

Мұзды бұрғылауға ғылыми себептермен алғашқы әрекетті жасаған Луи Агасиз 1840 жылы Unteraargletscher ішінде Альпі.[1] Бұл сол кездегі ғылыми ортаға түсініксіз болды мұздықтар ағып кетті,[1] және қашан Франц Йозеф Хюги Унтераарлглетчердегі үлкен тастың 1827-1836 ж.ж. аралығында 1315 м қозғалғанын көрсетті, скептиктер бұл тас мұздықпен төмен қарай жылжып кеткен болуы мүмкін деген пікір айтты.[2] Агасиз 1839 жылы мұздыққа барды,[3] Ол 1840 жылдың жазында қайтып оралды. Ол мұздықтың ішкі бөлігіне температуралық бақылаулар жасауды жоспарлап, осы мақсат үшін ұзындығы 25 фут (7,6 м) темір бұрғылау шыбығын әкелді.[1][4] Бұрғылаудың алғашқы әрекеті тамыз айының басында бірнеше сағат жұмыс істегеннен кейін тек 15 дюйм (15 см) прогресс жасады. Түнде жауған жаңбырдан кейін бұрғылау әлдеқайда тез жүрді: он бес минуттың ішінде бір фут (30 см) алға жылжып, саңылау ақыры 20 фут (6,1 м) тереңдікке жетті. Жақын жерде бұрғыланған тағы бір тесік 2,4 метрге жетті,[5] алты ағынды маркерді мұздықтың арғы жағына қою үшін бұрғыланды, мұны Агастис келесі жылға қарай жылжып, мұздықтың ағынын көрсететін болады деп ойлады. Ол сенді мұздықтар ағынының кеңею теориясы еріген сулардың мұздатуы мұздықтардың біртіндеп ұзаруына себеп болды деген пікір; Бұл теория судың шығыны көп болған жерде ағынның жылдамдығы үлкен болуы керек дегенді білдірді.[1]

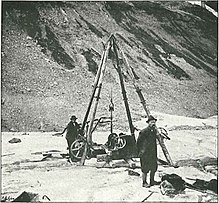

Агасиз 1841 жылы тамызда Unteraargletscher-ге оралды, бұл жолы ұңғымаларды бұрғылауға қолданылатын, әрқайсысының ұзындығы 15 фут (4,6 м) болатын 10 темір өзектен тұратын бұрғымен жабдықталған; ұзағырақ бұрғылауды қолмен пайдалану мүмкін емес еді, және оған өте қымбат тұратын тіреуіш керек еді. Ол мұздықтың қалыңдығын анықтайтын терең бұрғылауға үміттенген. Саңылаулар суға толы болған кезде бұрғылау тезірек жүретіндігін түсінгеннен кейін, тесіктерді оларды мұздықтағы көптеген кішігірім ағындардың бірімен сумен қамтамасыз ете алатындай етіп орналастырды. Мұның тесіктің түбінен мұздың жоңқаларын кетіруді жеңілдетудің қосымша пайдасы болды, өйткені олар бетіне көтеріліп, ағынмен алып кетті.[1][6] Бірінші саңылау 21 футқа жеткенде, бұрғылау шыбықтары ер адамдар қолдана алмайтындай дәрежеге жетті, сондықтан штатив құрастырылып, шкив орнатылды, сөйтіп бұрғылауды кабель арқылы көтеріп, түсіруге болатын.[1][6] Штативті аяқтауға бірнеше күн қажет болды, ал адамдар бұрғылауды қайтадан бастауға тырысқанда, бұрғылау енді жарты дюймге дейін жабылған тесікке енбейтіндігін біліп, оларды жаңа тесік бастауға мәжбүр етті . 1841 жылы қол жеткізілген ең терең тесік 140 фут (43 м) болды.[1][6]

1840 жылы орналастырылған ағын белгілері 1841 жылы орналасқан, бірақ ақпаратсыз болып шықты; сонша қардың ерігені соншалық, олардың барлығы мұздақтың үстінде жатты, бұл өздері ішіне енген мұздың қозғалысын дәлелдеу үшін пайдасыз болды. Алайда мұзға он сегіз фут тереңдік орнатылған баған әлі жеті футпен салынған Жер бетінен жоғары және 1841 жылдың қыркүйегінің басынан бастап көрінетін он фут. Агасиз терең тесіктерді бұрғылап, мұздықтың үстінен түзу сызыққа алты баған отырғызып, оның болуын қамтамасыз ету үшін қоршаған таулардағы анықталатын нүктелерге сілтеме жасай отырып өлшем жасады. олардың қозғалғанын біле алады.[7][8]

Бұл ағындық маркерлер 1842 жылы шілдеде Агтиссиз Унтераарлглетчерге оралған кезде де өз орнында болды, енді жарты ай формасын қалыптастырды; мұздың ортасында мұздың шетінен гөрі әлдеқайда тез ағатыны анық болды.[7][1 ескерту] Бұрғылау қайтадан кабельдік құрал тәсілімен 25 шілдеде басталды. Кейбір проблемалар туындады: жабдық бір сәтте сынып, оны жөндеуге тура келді; бірде ұңғыманың бір түнде бұрмаланғандығы және оны қайта бұруға тура келгені анықталды. Тесік тереңдей бастаған сайын, бұрғылау жабдықтарының салмағының артуы Агасизді кабельді тартатын ерлер санын сегізге дейін көбейтуге мәжбүр етті; сондықтан да олар күніне үш-төрт метр ғана көтере алды. Бұрғылау жалғасуда, зондтар алынды молиндер және 232 м және 150 м тереңдіктер табылды. Агасиз бұл өлшемдер қатал емес екенін түсінгенімен, өйткені көзге көрінбейтін кедергілер көрсеткіштерді бұрмалап жіберуі мүмкін, ол өз тобының мұздықтың түбіне бұрғылау жасау мүмкін емес екеніне сенімді болды және 200 футтан төмен бұрғыламауға шешім қабылдады ( 61 м). Кейін температураны өлшеу үшін 32,5 м және 16 м қосымша тесіктер бұрғыланды.[11]

19 ғасырдың аяғы

Блюмке мен Гесс

Агассиздің мұздық мұзында терең тесік бұрғылаудың үлкен қиындықтарын көрсетуі басқа зерттеушілерді осы бағыттағы одан әрі күш-жігерден бас тартты.[12] Бұл салада одан әрі ілгерілеушіліктерге онжылдықтар болды,[12] бірақ мұз бұрғылауға байланысты алғашқы екі патент 19 ғасырдың аяғында Америка Құрама Штаттарында тіркелген: 1873 жылы В.А. Кларк өзінің «Мұз айдайтын машиналарын жетілдіруге» патент алды, бұл оның мөлшеріне мүмкіндік берді. нақтыланған саңылау, ал 1883 жылы Р.Фицджералд түбіне кескіш пышақтары бекітілген цилиндрден жасалған қолмен жұмыс жасайтын бұрғыны патенттеді.[13]

1891 - 1893 жылдар аралығында Эрих фон Дригальский батыс Гренландияға екі экспедицияда болып, сол жерде қасық тасығышпен таяз тесіктерді бұрғылады: ұзындығы 75 см болатын қуыс болат цилиндр, төменгі жағында жұпты жүздері бар; тереңдігі 75 см-ден асатын тесіктерге ұзындығы бірдей түтіктер қосуға болады. Пышақтармен кесілген мұз цилиндрде ұсталды, оны мұз кесінділерін босату үшін мезгіл-мезгіл көтеріп отыруға болатын еді. Тесіктер мұздың жылжуын өлшеу үшін, оларға полюстер (көбінесе бамбук) салып, оларды қадағалап отырды. Ең үлкен тереңдік небары 2,25 м болды, бірақ фон Дригальски терең тесіктерді бұрғылау оңай болар еді деп түсіндірді; 0 ° температурадағы 1,5 м шұңқыр шамамен 20 минутты алды. Фон Дригальский басқа бұрғылау конструкцияларын қабылдады, бірақ қасық тасығышты ең тиімді деп тапты.[13][14]

1894 жылы Адольф Блюмке мен Ганс Гесс экспедициялар сериясын бастады Hintereisferner. Агасиз экспедициясынан бері тереңдікте мұзды бұрғылауға тырыспағандықтан, олардан үйренетін соңғы мысалдар болмаған, сондықтан олар 1893–1894 жылдың қысында сыра зауытының мұзды жертөлесінде бұрғылау сызбаларымен тәжірибе жасады. Басынан бастап олар перкуссиялық бұрғылауға қарсы шешім қабылдады және фон Дригальски Гренландияға өткізген жаттығулардың бірін тексерді. Олар сондай-ақ фон Дригальскийдің қасық тасығышының көшірмесін жасады, бірақ оны пайдалану формасын сақтау үшін оны әлсіз деп тапты. Олар бұрандалы бұранданы бұрау үшін бұрандалы бұранданы айналдыру үшін қол иіндісін қолданды. Олардың бастапқы жоспары мұз кесінділерін кепілдікпен алып тастау болды, бірақ олар бұл жоспардан бірден бас тартты;[15] оның орнына шнек аралықпен ұңғымадан алынып тасталды, шламды алып кету үшін саңылауға су жіберу үшін түтік салынды. Бұл мүлдем жаңа тәсіл болды және әдісті жетілдіру үшін бірнеше сынақ пен қателік қажет болды. 40 м тереңдікке қол жеткізілді.[16][17] Келесі жылы олар шнекті өзгертті, сөйтіп бұрғыдағы тесіктен су шығып, шламды бұрғының сыртына айналдырып тастады. бұл кесінділерді тазарту үшін бұрғылауды алып тастау қажеттілігін жойды.[17] Бұрғылауға күніне жеті сағатты ғана пайдалануға болатын, өйткені мұздықта бір түнде аққан су болмаған.[18]

Бұрғылау ұңғымасы деформацияланғандықтан болар, мұзда жиі сыналатын болды, сонымен қатар мұздағы жыныстарды кездестіру жиі кездесетін, оларды мұз кесінділерін тазартқан суда жер бетіне шыққан тас сынықтары арқылы анықтауға болатын. . Ең қиын мәселе - мұздағы бос жерлерді бұрғылау. Бос орынның түбінде жаңа ұңғыма басталады; егер қуыс бұрғылау құбыры арқылы тартылған су құбырдың айналасына күштеп салынғаннан кейін ұңғымадан ағып кететіндей болса, онда бұрғылауды жалғастыруға болады; егер олай болмаса, шламдар ұңғыманың айналасында жиналып, ақырында одан әрі алға жылжу мүмкін болмай қалады. Блюмке мен Гесс жүгіруге тырысты қаптама құбыры су мен шламдар жер бетіне шығуы үшін, қуыс арқылы төмен қарай жылжытыңыз, бірақ бұл сәтсіз болды және мәселе туындаған сайын іске асыру үшін шешім өте қымбат болар еді.[19]

1899 жылы мұздықтың төсегіне тереңдігі 66 м және 85 м болатын екі жерде жетті және бұл жетістік Неміс және австриялық альпілік клуб жүргізіліп жатқан жұмыстарды қаржыландыру және бұрғылау аппараттарының жетілдірілген нұсқасын құру үшін ерте экспедицияларға субсидия берген 1901 ж. пайда болды. Ең басты жақсартқыш - шнекке бүйір кесу жиектерін қосу, саңылауды қайта қалпына келтіруге мүмкіндік беру және егер ол деформацияланған тесікке қайта салынған.[17] Жабдықтың салмағы 4000 кг болатын, бұл биік таулардағы көлік шығындарымен және үлкен команданы жалдау қажеттілігімен олардың әдісін қымбатқа түсірді,[20] Блюмке мен Гесс олардың тәсілдері басқа командалардың көбеюі үшін өте қымбат болмайды деп болжады.[21][2 ескерту] Блюмке мен Гессстің 1905 жылы жарияланған жұмыстарына шолу жасағанда, Пол Меркэнтон бұрғылау бұрылысы мен су сорғысын қуаттандыратын бензин қозғалтқышы табиғи жетілдірулер болады деп ұсынды. Сорғының жұмысы тереңдіктен едәуір қиындай түскені байқалды, және ең терең тесіктерге айдауды жалғастыру үшін сегіз адамға дейін қажет болды. Меркантон сонымен қатар Блумке мен Гесстің бұрғысы кесінділерді тазарту үшін минутына 60 литрге жуық уақытты қажет ететіндігін, ал тұрақты Дутоитпен жұмыс істеген ұқсас бұрғылау сол мақсат үшін судың тек 5% ғана қажет екенін байқады және ол судың ағып кетуін орналастыруды ұсынды. бұрғылау битінің түбіндегі су бұрғылау битінің айналасындағы қарама-қайшы су ағынын азайту және суға деген қажеттілікті азайтудың кілті болды.[23]

Тесіктер Блюмке мен Гесс мұздықтың формасы мен болжамды тереңдігі бойынша жасаған есептеулерін тексеру үшін бұрғыланды және нәтижелер олардың күткенімен өте жақсы сәйкес келді.[21] Барлығы Блюмке мен Гесс 1895-1909 жылдар аралығында мұзды қабатқа дейінгі 11 тесікті бітірді және мұздыққа енбеген көптеген тесіктерді бұрғылады. Олардың бұрғыланған ең терең шұңқыры 224 м.[24] 1933 жылы 1901 жылғы ұңғымада қалған корпус қайта табылды; сол уақытқа қарай тесік алға қарай қисайып, мұздықтың ағын жылдамдығы жер бетінде ең үлкен болғандығын көрсетті.[25][26]

Валлот, Дутойт және Меркантон

1897 жылы Émile Vallot Mer-де-Glace-де биіктігі 3 м кабельдік құралды болат бұрғылаушы көмегімен крест тәрізді жүздері бар және салмағы 7 кг болатын 25 метрлік тесікті бұрғылады. Бұл тиімді бұрғылау үшін өте жеңіл болды және бірінші күні тек 1 метр алға жылжу болды. 20 кг темір таяқша қосылып, прогресс сағатына 2 м-ге дейін жақсарды. Арқанды тесіктің үстінен бұру үшін таяқша қолданылған, ал ол бұралмаған кезде дөңгелек тесікті кесіп тастаған; тесіктің диаметрі 6 см. Арқан да артқа тартылып, құлап түсті, сондықтан бұрғылауда перкуссия мен айналмалы кесудің тіркесімі қолданылды. Бұрғылау алаңы ұңғыманың түбінде босатылған мұз сынықтарын бұрғылау процесінде тасып кету үшін ұңғыманы үнемі сумен толықтыруға болатындай етіп, кішкене ағынға жақын деп таңдалды; бұрғылау циклін қатарынан үш соққы сайын он соққы сайын жоғары көтеру арқылы мұз чиптеріне тесікке көтерілуге шақырылды. Бұрғылау қондырғысы күн сайын орнында қатып қалмас үшін тесіктен алынып тасталынды.[12][27]

Тесік 20,5 м жеткенде, 20 кг таяқша тесіктегі судың тежеу әсеріне қарсы тұруға жетіспеді және прогресс сағатына 1 м-ге дейін баяулады. Chamonix-те салмағы 40 кг болатын жаңа таяқша соғылды, бұл жылдамдықты сағатына 2,8 м дейін артқа шығарды, бірақ 25 м-де бұрғылау ұшы түбіне жақын тесікке тұрып қалды. Валлот мұзды еріту үшін шұңқырға тұз құйып жіберді және оны босату үшін темір бөлігін төмен түсірді, бірақ тесіктен бас тартуға тура келді. Эмиль Валлоттың ұлы, Джозеф Валлот, бұрғылау жобасының сипаттамасын жазып, сәтті болу үшін мұзды бұрғылау мүмкіндігінше тезірек, мүмкін ауысыммен жүргізілуі керек, және бұрғылаудың кез-келген деформациясы бұрғылау ретінде түзетілуі үшін бұрғылаудың шеттері болуы керек деген қорытындыға келді. тесікке қайта енгізілді, бұл бұрғылау битінің бұл жағдайда болуын болдырмауға мүмкіндік берді.[12][27]

Тұрақты Дутоит және Пол-Луи Меркантон бойынша эксперименттер жүргізді Үштік мұздық туындаған проблемаға жауап ретінде 1900 ж Швейцария жаратылыстану ғылымдары қоғамы 1899 жылы олардың жылдық Prix Schläfli, ғылыми сыйлық. Мәселе мұздықтың ағынының ішкі жылдамдығын, оған тесік бұрғылау және шыбықтар салу арқылы анықтау болды. Дутоит пен Меркантон Гесс пен Блюмкенің жұмысы туралы естімеген, бірақ дербес ұқсас жобаны ойлап тапты, су қуыс бұрғылау құбырына су құйып жіберді және бұрғылау ұңғымасынан тесікке мұз кесінділерін тасуға мәжбүр етті. Кейбір алдын ала сынақтардан кейін олар 1900 жылдың қыркүйегінде мұздыққа оралып, 4 сағаттық бұрғылау жүргізіп 12 метр тереңдікке жетті.[16][28] Олардың жұмысы оларға 1901 жылы Шлафли При сыйлығын жеңіп алды.[29][30]

Ерте 20ші ғасыр

19 ғасырдың аяғында мұзды мұзда бірнеше метрден аспайтын тесіктер жасауға арналған құралдар қол жетімді болды. Тереңірек тесіктерді бұрғылау бойынша зерттеулер жалғасты; ішінара ғылыми себептерге байланысты, мысалы мұздықтардың қозғалысын түсіну, сонымен қатар практикалық мақсаттар үшін. 1892 жылы Тете-Русе мұздығының құлауы 200 000 м3 су, соның салдарынан 200-ден астам адам қаза тапты, су тасқыны нәтижесінде мұздықтардағы су қалталарын зерттеу; сонымен қатар мұздықтар жыл сайын шығарылатын еріген сулардан бере алатын гидроэлектр энергиясына деген қызығушылық арта түсті.[31]

Флусин мен Бернард

1900 жылы Бернард бұрғылауды бастады Тете Русс мұздығы, Француз су және орман департаментінің нұсқауымен. Ол темір түтіктің ұшында өткір қиғаш етіп, перкуссиялық тәсілді қолданудан бастады. Тереңдігі 18 м-ден аспайтын 25 тесікке 226 м бұрғылау жүргізілді. Келесі жылы дәл сол құралдар мұздықтағы қатты мұз аймағында өте баяу ілгерілеу кезінде қолданылды; 11,5 м шұңқырды бұрғылауға 10 сағат қажет болды. 1902 жылы конусты сегіз қырлы штанганың ұшында крест тәрізді кескіш пышақпен алмастырды және одан әрі ілгерілеу мүмкін болмай тұрып 20 сағат ішінде 16,4 м шұңқыр бұрғыланды. Осы кезде Бернард Блюмке мен Гесс жұмысынан хабардар болды және Гессадан олардың бұрғылауының дизайны туралы ақпарат алды. 1903 жылы ол жаңа дизайнмен бұрғылауды бастады, бірақ оны өндіруде ақаулар болды, бұл елеулі прогресті болдырмады. Бұрғы қыс мезгілінде өзгертіліп, 1904 жылы ол 28 сағат ішінде 32,5 м шұңқырды бұрғылай алды. Тесікте бірнеше тастар кездесті, және бұрғылау жалғаспас бұрын оларды соққы әдісімен бұзды.[32] Пол Мугин, Шамберидегі су және орман инспекторы, бұрғылау үшін қыздырылған темір торларды қолдануды ұсынды: штангалардың ұштары қызғанға дейін қызып, ұңғымаға түсіп кетті. Сағатына 3 м прогресс осы тәсілмен алынды.[33]

Джордж Флусин Бернармен Хинтерейсфернерде 1906 жылы Блюмке мен Гесспен бірге олардың жабдықтарының қолданылуын қадағалады. Олар бұрғылау тиімділігі, ең жоғары 30 м шұңқырда 11-12 м / сағ дейін жетуі мүмкін, тереңдікпен біртіндеп төмендейтінін және үлкен тереңдікте әлдеқайда баяу болатынын атап өтті. Бұл ішінара терең ойықтарда тиімділігі төмендейтін сорғыға байланысты болды; бұл тесікті мұз кесінділерінен тазартуды қиындатты.[34]

Ерте экспедицияларда мұз бұрғылау

1900-1902 жылдар аралығында Аксель Гамберг қардың жиналуы мен жоғалуын зерттеу үшін шведтік Лапландиядағы мұздықтарды аралады және өлшеуіш таяқшаларды орналастыру үшін тесіктер бұрғылады, содан кейін кейінгі жылдары қар қалыңдығының өзгеруін анықтауға болады. Ол тау жыныстарын бұрғылауға қолданылатын қашау бұрғысын қолданды және тесікті суға толтыру арқылы ойық түбінен кесінділерді алып тастады. Салмақты үнемдеу үшін Гамбергте болатпен қапталған күл сияқты мықты ағаштан жасалған бұрғылар болған; ол 1904 жылы бес жыл бойы бұрғылаушы болғанын, тек қашауды бекітетін металды және кейбір бұрандаларды ауыстыруы керек екенін хабарлады. Құралмен тәжірибесі бар адамның қолында бір сағат ішінде 4 м тереңдіктегі тесік жасалуы мүмкін.[37][13]

A Антарктикаға неміс экспедициясы Фон Дригальский бастаған 1902 жылы мұз айдынында температура өлшеу үшін тесіктер бұрғылаған. Олар Hintereisferner-де қолданылған бұрандалы болат құбырларға бекітілген бұрандалы шнекті қолданды. Мұзды бұрғылау үшін қасық-бұрғылаушыны пайдалану өте қиын болды, бірақ ол мұз кесінділерін жинақталғаннан кейін прогресс баяулағанша алып тастау үшін пайдаланылды. Фон Дригальский Альпіде бұрғыланған саңылаулар кесінділерді тасу үшін суды пайдаланғанын білген, бірақ ол бұрғылап жатқан мұз суық болғандықтан, шұңқырдағы кез-келген су тез қатып қалатын еді. Тереңдігі 30 м-ге жететін бірнеше тесік бұрғыланды; фон Дригальский 15 м тереңдікке жету салыстырмалы түрде оңай болғанын жазды, бірақ одан тыс уақытта бұл әлдеқайда қиын жұмыс болды. Мәселенің бір бөлігі бұрғылау ұзартылған кезде, бірнеше бұрандалы қосылыстармен бұрғылауды тесіктің жоғарғы жағында айналдыру тесіктің түбінде сонша айналуға әкелмеді.[36][35]

1912 жылы, Альфред Вегенер және Йохан Питер Кох қысты Гренландияда мұз үстінде өткізді. Вегенер өзімен бірге қолмен шнекті алып, температура көрсеткіштерін өлшеу үшін 25 м шұңқырды бұрғылады. Неміс геологы Ганс Филипп мұздықтардың сынамаларын алу үшін қасық тасығышты жасап шығарды және механизмін 1920 жылғы қағазда сипаттады; оны тез босатуға мүмкіндік беретін тез босату механизмі болды. 1934 жылы Норвегия-Швеция Шпицберген экспедициясы кезінде, Харальд Свердруп және Ханс Ахман тереңдігі 15 м-ден аспайтын бірнеше тесік бұрғыланды. Олар Филипп сипаттағанға ұқсас қасық тасығышты қолданды, сонымен қатар кесілген поршеньге ұқсас өзек бұрғысы бар мұз өзектерін алды.[38]

Ерте қардан сынамалар

Алғашқы қар сынамасын жасаған Джеймс Э. шіркеуі 1908–1909 жж. қыста, қардың үлгісін алу үшін Роза тауы, ішінде Карсон жотасы АҚШ-тың батысында. Ол диаметрі 1,75 диаметрі бар кескіш басымен бекітілген болат түтікшеден тұрды және осыған ұқсас жүйелер ХХІ ғасырда қолданылып келеді.[39][40] Бастапқы кескіштің бас дизайны қарды сынама алушының корпусына сығуға әкелді, нәтижесінде қардың тығыздығы жүйелі түрде 10% шамадан тыс бағаланды.[39]

1930 жылдарға дейін шіркеудің қар сынамаларын жасайтын дизайнын жақсарту басталды Джордж Д. Клайд түтік ішіндегі бір дюйм су дәл бір унция болатындай етіп өлшемдерді кім өзгертті; бұл сынаманы пайдаланушыға толтырылған сынаманы өлшеу арқылы қардың сәйкес келетін су тереңдігін оңай анықтауға мүмкіндік берді. Клайдтың сынамасы болаттан гөрі алюминийден жасалған, оның салмағы үштен екіге азайған.[39][41] 1935 жылы АҚШ Топырақты сақтау қызметі қар үлгіні алу формасын стандарттады, оны терең қардың үлгісі үшін қосымша бөлімдер қосуға болатын етіп модульдейді. Бұл енді «Федералдық қар сынамасы» деп аталады.[39]

Бірінші термиялық жаттығулар

Ерте термалды бұрғылау жүргізілді Хосанд мұздығы және Миаж мұздығы Марио Кальциатидің 1942 ж.; ол бұрғылау ұңғымасын ыстық сумен қыздыру арқылы жұмыс істеді, оған ағаш жанатын қазандықтан сорып жіберді.[42][43][44] Кальциати мұздықтың төсегіне сағатына 3-тен 4 м-ге дейін 119 м жылдамдықпен жетті. Бұрғыланған ең терең тесік 125 м.[44][43] Дәл сол процесс кейін онжылдықта қолданылды Énergie Ouest Suisse төсегіне дейін он бес тесік бұрғылау Горнер мұздығы,[45] 1948 жылы А.Сюсструнктың сейсмографиямен анықтаған тереңдігін растайтын.[46]

1946 жылы мамырда Швейцарияда электротермиялық бұрғы патенттелген Рене Коечлин; ол бұрғылау ішіндегі сұйықтықты электрлік қыздыру арқылы жұмыс істеді, содан кейін сорғы ретінде жұмыс істейтін винттің көмегімен мұзбен байланыста бетіне айналды. Бүкіл механизм бұрғылауды қолдайтын және электр тогын қамтамасыз ететін кабельге бекітілді.[42][47] Бұрғылаудың теориялық жылдамдығы 2,1 м / сағ құрады. 1951 жылғы қағаз Électricité de France инженерлер Коечлиннің бұрғысы Швейцарияда қолданылғанын хабарлады, бірақ ешқандай мәлімет бермеді.[48]

Юнгфраухох және Севард мұздығы

1938 жылы Джеральд Селигман, Том Хьюз және Макс Перуц температура көрсеткіштерін өлшеу үшін Юнгфраухоға барды; олардың мақсаты қардың фирнға, одан әрі мұзға тереңдеуімен ауысуын зерттеу болды. Олар біліктерді 20 м тереңдікте қолмен қазды, сонымен қатар екі түрлі конструкциядағы шнектермен саңылауларды ойықтады, соның ішінде Ханс Ахлманның кеңесіне негізделген.[38][49] 1948 жылы Перуц Джунгфрауға оралды, мұндағы мұздық ағынын зерттеу жобасын басқарды Юнгфрауфирн. Жоспар бойынша, мұздықтың түбіне тесік бұрғылау, тесікке болат түтікшені орналастыру, содан кейін оны келесі екі жыл ішінде қайта қарап, түтікшенің әр түрлі тереңдікке бейімділігін өлшеу қажет болды. Мұздың ағынының жылдамдығы мұздық бетінен тереңдікке қарай қалай өзгеретінін анықтайтын еді. General Electric бұрғының ұшына арналған электр қыздырғыш элементін жобалаумен айналысқан, бірақ оны кеш жеткізген; Перутц бұл жерден пакетті алуға тура келді Виктория станциясы Келіңіздер сол жүк ол Ұлыбританиядан Швейцарияға кетіп бара жатқанда. Пакет одан әрі қарай пойыздағы басқа чемодандардың үстіне тірелген Кале Перутц чемоданды түсіру кезінде оны кездейсоқ пойыз терезесінен құлатып алды. Оның команда мүшелерінің бірі Калеға оралды және жергілікті ұйымдастырды Скауттар пакетті іздеу үшін, бірақ ол ешқашан қалпына келтірілмеген. Перуц жеткен кезде Сфинкс обсерваториясы (зерттеу станциясы Юнгфрауох ) оған станция бастығы өндірістік фирма Edur A.G.-ге хабарласуға кеңес берді Берн;[3 ескерту] Edur сыра бөшкелерін ашу үшін электротермиялық құрал-саймандар шығарды және тез қанағаттанарлық бұрғылау ұшын жасай алды. Перуц жаңа бұрғылау ұшымен оралды, ол Бернге барған кезде шаңғымен сырғанауды үйренуді қалдырған екі аспиранты екеуінің де аяқтарын сындырды. Ол сендіре алды Андре Роч, сол кезде кім болған Қар мен қар көшкінін зерттеу институты кезінде Weissfluhjoch, жобаға қосылу үшін Кембриджден де көптеген студенттер жіберілді.[24][52][50]

Ыстыққа төзімді сазға пісірілген үш тантал катушкаларынан құралған қыздыру элементі тесіктің ішкі қабатын құрайтын болат түтікшенің соңына бұралып бекітіліп, тесіктің үстіндегі бұрғылауды тоқтата тұру үшін штатив орнатылды. Элемент 330 В кернеуінде 2,5 кВт қуатты шығарды және болат түтікке түсіп тұрған кабель арқылы жұмыс істеді. Ол Сфинкс обсерваториясындағы қуатқа қардың үстінен салынған кабель арқылы қосылды. Бұрғылау 1948 жылдың шілдесінде басталды, екі аптадан кейін мұздықтың түбіне 137 м тереңдікте ойық ойдағыдай бұрғыланды. Қосымша кідірістер болды: екі рет түтікті тесіктен шығарып алу керек болды - бір рет құлаған кілтін алып тастау үшін және бір рет қыздырғыш элементтің күйіп қалуы. Инклинометр көрсеткіштері 1948 жылдың тамыз және қыркүйек айларында, тағы 1949 жылдың қазанында және 1950 жылдың қыркүйегінде қабылданды; нәтижелер көрсеткендей, бұрғылау ұңғымасы уақыт өткен сайын алға қарай иіліп, мұздың жылдамдығы төсектен төсекке қарай төмендегенін білдіреді.[24][52][50]

Сондай-ақ, 1948 ж Солтүстік Американың Арктикалық институты экспедициясының демеушісі болды Seward мұздығы ішінде Юкон, Канадада, Роберт П.Шарп бастаған. Экспедицияның мақсаты мұздықтың температурасын жердің астынан әр түрлі тереңдікте өлшеу болды, ал термометрлер орналастырылған ұңғымаларды жасау үшін электротермиялық бұрғылау қолданылды. Саңылаулар алюминий құбырымен 25 футтан аспайтын тереңдікте тесіліп, тереңдіктен төмен бұрғылау қолданылды. Бұрғылау бұрғысы электр тогы арқылы бұрғылау құбыры арқылы ауыр кабельмен өткізіледі; басқа өткізгіш бұрғылау құбырының өзі болды. Бұрғылау дизайны тиімді болып шықты, ал ең терең тесік 204 фут болды; Шарп қажет болған жағдайда әлдеқайда терең тесіктерді бұрғылау оңай болар еді деп есептеді. Экспедиция 1949 жылы сол құрал-жабдықпен мұздыққа оралды, одан әрі тесіктер бұрғылап, максималды тереңдігі 72 фут болды.[53]

Басқа ерте термиялық жаттығулар және алғашқы мұз өзектері

The Polaires Françaises экспедициясы (EPF) Гренландияға 40-шы жылдардың аяғы мен 50-ші жылдардың басында бірнеше экспедициялар жіберді. 1949 жылы олар мұз өзегін қалпына келтірген алғашқы команда болды; термиялық бұрғылау IV лагерінде диаметрі 8 см мұз өзегін алу үшін 50 м шұңқырды бұрғылау үшін қолданылды. Келесі жылы Гренландияда, VI лагерьде, Милцентте және Сентраль Центральда басқа ядролар бұрғыланды; оның үшеуі үшін термиялық бұрғы қолданылған.[54][55]

1949 жылы Альпіде электротермиялық бұрғы орналастырылды Ксавье Ракт-Маду және Мер де Гласқа шолу жасайтын Л.Рейно және Л. Électricité de France оны су электр энергиясының көзі ретінде пайдалануға болатындығын анықтау. 1944 жылғы тәжірибелер мұз арқылы туннельдерді тазарту үшін жарылғыш заттарды қолдану тиімді еместігін көрсетті; мұздықтың ішкі бөлігінің кейбір өтпелері қазу арқылы ашылды, бірақ мұздың қысымы мен пластикасына байланысты бірнеше күн жабылды, бұл тоннельдерді ағашпен бекітуге тырысқандықты басып озды. 1949 жылдың жазында Ракт-Маду мен Рейно мұздыққа конустық пішінді, ұзындығы 1 м резистордан тұратын термиялық бұрғымен оралды, максималды диаметрі 50 мм. Бұл ұңғыма үстіндегі штатив арқылы кабельден тоқтатылды және тамаша жағдайда бір сағат ішінде 24 м бұрғылауға мүмкіндік берді.[56][42]

1951 жылдың жазында Калифорния технологиялық институтының қызметкері Роберт Шарп Перуцтың мұздық ағыны тәжірибесін қайталап шығарды, мұнда ыстық нүкте бар термиялық бұрғылау қолданылды. Маласпина мұздығы Аляскада. Тесік алюминий құбырымен қапталған; сол кездегі мұздықтың қалыңдығы 595 м болды, бірақ шұңқыр жұмыс істемей қалғандықтан, тесік 305 м-ге тоқтады.[57] Сол жазда Кальциатидің жобасына негізделген термиялық бұрғылауды Питер Кассер Гидротехника және жер жұмыстары институтында, Zurich Technische Hochschule (ETH Цюрих). Бұрғылау мұздықтарда үлестерді өлшеу үшін үлестерді орнатуға көмектесу үшін жасалған; кейбір Альпі мұздықтары бір жыл ішінде 15 м-ге дейін мұзды жоғалтады, сондықтан пайдалы болу үшін ұзаққа созылатын қазықтарды салу үшін саңылаулар шамамен 30 м тереңдікте болуы керек. Қазандық суды 80 ° C-тан жоғары қыздырды, ал сорғы оны құбырлар арқылы бұрғылаудың металл ұшына айналдырды, содан кейін қазандыққа оралды. Салқындатылған судың қазандыққа оралмай тұрып қату қаупін азайту үшін этиленгликоль антифриздік қоспа ретінде қолданылды. Бұрғылау алғаш рет 1951 жылы Алец мұздығында сыналды, мұнда орта есеппен 13 м / сағ жылдамдықпен 180 м саңылаулар бұрғыланды, содан кейін Альпіде кеңінен қолданылды. 1958 және 1959 жылдары Батыс Гренландияда қолданылды Халықаралық Гляциологиялық Гренландия экспедициясы (EGIG), бөлігі Халықаралық геофизикалық жыл.[58][59]

Саскачеван мұздығында скважиналарды бұрғылауға және оларды алюминий құбырымен қаптауға, инклинометрді зерттеу үшін бірқатар әрекеттер жасалды. Бұрғы электрлік нүкте болды. 1952 жылы үш тесік жасалды; жабдықтар істен шыққан кезде немесе жедел нүкте одан әрі ене алмай қалған кезде, барлығы 85-тен 155 футқа дейінгі тереңдікте қалдырылды. Келесі жылы 395 фут тереңдіктегі тесік жоғалды, оның бір себебі мұз қозғалысы саңылауды қысады; 1954 жылы тағы екі тесік 238 футтан және 290 футтан бас тартылды. Үш қаптама жиынтығы орналастырылды: 1952 ең терең шұңқырға және 1954 екі тесікке. 1954 жылғы құбырлардың бірі судың ағып кетуіне байланысты жоғалған, ал қалған құбырлар бойынша өлшемдер жүргізілген; 1952 жылы құбыр 1954 жылы қайта зерттелген.[60]

1950 жж

FEL, ACFEL, SIPRE және SIPRE шнегі

АҚШ армиясының Инженерлер корпусы Екінші дүниежүзілік соғыс кезінде Аляскадағы қызметін едәуір кеңейтті және бірнеше ішкі ұйымдар кездескен мәселелерді шешу үшін пайда болды. Бостонда Корпустың Жаңа Англия дивизиясының құрамында ұшу-қону жолақтарындағы аяз проблемаларын зерттейтін топырақ зертханасы құрылды; ол 40-шы жылдардың ортасында «деп аталатын жеке тұлғаға айналды Аяз эффектілері зертханасы (FEL). Миннесота штатындағы Сент-Полда орналасқан жеке мәңгі тоң дивизиясы 1945 жылы қаңтарда құрылды.[61] АҚШ Әскери-теңіз күштері Океанография дивизиясының өтініші бойынша,[62] FEL 1948 жылы мұзды бұрғылау және кернеу және далада мұздың қасиеттерін өлшеу үшін қолданылатын портативті жинақ жасау мақсатында мұз механикасын сынауды бастады.[61][63] Әскери-теңіз күштері бұл жинақты мұзға қонуы мүмкін шағын ұшақпен көтере алатындай жеңіл болатындығын, сондықтан оны тез әрі оңай орналастыруды көздеді.[62] Нәтижесінде FEL 1950 мақаласында сипаттаған Мұз Механикасы сынағының жиынтығы болды, оны далада теңіз флоты және кейбір ғылыми зерттеушілер қолданды. Жинаққа диаметрі 3 дюймді құрайтын шнек кірді.[61][63] FEL зерттеушілері өзектердің баррельінің негізін аздап жіңішкерту керек деп тапты, олар кесінділер өзек баррелінің сыртына қарай жылжиды, сонда олар шнек ұшуларын жүргізе алады; онсыз, кесінділер өзектің бөшкесінде, өзектің айналасында жиналып, одан әрі ілгерілеуге кедергі келтіреді.[64] Сол зерттеу сонымен қатар бұрандалы емес шнектердің конструкцияларын бағалады және 20 ° саңылау бұрышы төмен кесу күшін қажет етпейтін жақсы кесу әрекетін тудыратындығын анықтады. Қалың және жіңішке кесу жиектері де тиімді деп табылды. Өте суық жағдайда мұз кесінділері шнектен түсіп, прогресті тежейтіндіктен, шнектен түсіп кететіні анықталды, сондықтан кесу жиегіне жақын жерде кішкене қоршау қосылды: кесінділер оның жанынан жоғары жылжи алады, бірақ оның артына құлап түсе алмады.[65][66] Тығыздалмаған шнектің оңай иілуге және тесікке кептелуге бейім екендігі анықталған кезде, бірақ ағытқыш шнек бұл проблемадан зардап шекпегені анықталды, саңылаусыз шнектің дамуы тоқтады, ал соңғы сынақ жиынтығына тек бұрандалы шнек.[67]

Сонымен қатар, 1949 жылы қар мен мұзға қатысты тағы бір армиялық ұйым құрылды: Қар, мұз және мәңгі мұзды зерттеу мекемесі (SIPRE). SIPRE әуелі Вашингтонда орналасты, бірақ көп ұзамай Сент-Полға, содан кейін 1951 жылы қоныс аударды Уилметт, Иллинойс, Чикагодан тыс жерде.[68] 1953 жылы FEL пермафрост бөлімімен біріктіріліп Арктикалық құрылыс және аяз эффектілері зертханасы (ACFEL).[69] 1950 жылдары SIPRE ACFEL шнегінің өзгертілген нұсқасын шығарды;[4 ескерту] бұл нұсқа әдетте SIPRE шнек ретінде белгілі.[70][71] It was tested on ice island Т-3 in the Arctic, which was occupied by Canadian and US research staff for much of the period from 1952 to 1955.[72][71] The SIPRE auger has remained in wide use ever since, despite the later development of other augers that addressed weaknesses in the SIPRE design.[73][70] The auger produces cores up to about 0.6 m; longer runs are possible, but lead to excess cuttings accumulating above the barrel, which risks jamming the auger in the hole when it is extracted. It was originally designed to be hand-operated, but has often been used with motor drives. Five 1 m extension rods were provided with the standard auger kit; more could be added as needed for deeper holes.[70]

Early rotary drilling and more ice cores

The use of conventional rotary drilling rigs to drill in ice began in 1950, with several expeditions using this drilling approach that year. The EPF drilled holes of 126 m and 151 m, at Camp VI and Station Centrale respectively, with a rotary rig, with no drilling fluid; cores were retrieved from both holes. A hole 30 m deep was drilled by a one-ton plunger which produced a hole 0.8 m in diameter, which allowed a man to be lowered into the hole to study the stratigraphy.[54][55]

Ract-Madoux and Reynaud's thermal drilling on the Mer de Glace in 1949 was interrupted by crevasses, moraines, or air pockets, so when the expedition returned to the glacier in 1950 they switched to mechanical drilling, with a motor-driven rotary drill using an auger as the drillbit, and completed a 114 m hole, before reaching the bed of the glacier at four separate locations, the deepest of which was 284 m—a record depth at that time.[56][42] The augers were similar in form to Blümcke and Hess's auger from the early part of the century, and Ract-Madoux and Reynaud made several modifications to the design over the course of their expedition.[56][42] Attempts to switch to different drillbits to penetrate moraine material they encountered were unsuccessful, and a new hole was begun instead in these cases. As with Blümcke and Hess, an air gap that did not allow the water to clear the ice cuttings was fatal to drilling, and usually led to the borehole being abandoned. In some cases it was possible to clear a plug of ice by injecting hot water into the hole.[74][42] On the night of 27 August 1950 a mudflow covered the drilling site, burying the equipment; it took the team eight days to free the equipment and start drilling again.[75]

An expedition to Баффин аралы in 1950, led by P.D. Baird of the Arctic Institute, used both thermal and rotary drilling; the thermal drill was equipped with two different methods of heating an aluminium tip—one a commercially supplied heating unit, and the other designed for the purpose. A depth of 70 ft was reached after some experimentation with different approaches. The rotary drilling gear included a saw-toothed coring bit, with spiral slots intended to aid the passage of ice cuttings back up the hole. The cores were retrieved frozen into the steel coring tube, and were extracted by briefly warming the tube in the exhaust gases from the rotary drill engine.[76]

In April and May 1950 the Норвегия-Британ-Швеция Антарктикалық экспедициясы used a rotary drill with no drilling fluid to drill holes for temperature measurement on the Мұзды сөреге арналған сөре, to a maximum depth of 45 m. In July drilling to obtain a deep ice core was begun; progress stopped at 50 m at the end of August because of seasonal conditions. The hole was extended to 100 m when drilling resumed. It was found that the standard mineral drillbit jammed with ice very easily, so every other tooth was ground away, which improved the performance. Obtaining the ice cores added a great deal to the time required for drilling: a typical drilling run would require about an hour of lowering the drill string into the hole, pausing after each drill pipe was lowered to screw another pipe onto the top of the string; then a few minutes of drilling; and then one or more hours of pulling the string back out, unscrewing each drill pipe in turn. The cores were extremely difficult to retrieve from the core barrel, and were very poor quality, consisting of ice chips.[54]

In 1950 Maynard Miller took rotary drilling equipment weighing over 7 tons to the Taku glacier, and drilled multiple holes, both to investigate glacial flow by placing an aluminium tube in a borehole and measuring the inclination of the tube with depth over time, as Perutz's team had done on the Jungfraufirn, and also to measure temperature and retrieve ice cores, mostly from 150–292 ft deep. Miller used water to flush cuttings from the hole, but also tested drilling efficiency in a dry hole and with various different auger bits.[54][24][77] In 1952 and 1953 Miller used a hand drill on the Taku glacier to drill cores down to a few metres in depth; this was a toothed drill with no flights to remove the cuttings, a design that has been found to be low efficiency, as the cuttings interfere with the continued drilling action of the teeth.[78]

In 1956 and 1957 the АҚШ армиясының инженерлер корпусы used a rotary rig to drill for ice cores at Site 2 in Greenland, as part of their Greenland Research and Development Program. The drill was set up at the bottom of a 4.5 m trench, with an 11.5 m mast to allow the use of 6 m pipes and core barrels. An air compressor was set up to clear the ice cuttings by air circulation; it produced air that could be as hot as 120 °C, so to prevent the hole walls and the ice core from melting, a heat exchanger was set up that brought the air down to 12 °C of the ambient temperature. The cores recovered were in reasonably good condition, with about 50% of the cored depth yielding unbroken cores. At 296 m it was decided to drill without coring in order to reach a greater depth more quickly (since non-coring drilling did not require slow roundtrips to remove the cores), and to start coring again once the hole reached 450 m. A tricone bit was used for the non-coring drilling, but it soon became stuck and could not be released. The hole was abandoned at 305 m. The following summer a new hole was begun in the same trench, again using air circulation to clear cuttings. Vibration of the drill bit and core barrel caused the cores to shatter during drilling, so a heavy drill collar was added to the drillstring, just above the core barrel, which improved core quality. At 305 m depth coring was stopped and the hole was continued to 406.5 m, with two more cores retrieved at 352 m and 401 m.[79]

Another SIPRE project, this time in combination with the IGY, used a rotary rig identical to the rig used at Site 2 to drill at Берд станциясы in West Antarctica. Drilling lasted from 16 December 1957 to 26 January 1958, with casing down to 35 m and cores retrieved down to 309 m. The total weight of all the drilling equipment was nearly 46 t.[80] In February 1958 the equipment was moved to Little America V, where it was used to drill a 254.2 m hole in the Ross Ice Shelf, a few metres short of the bottom of the shelf. Air circulation was again used to clear the cuttings for most of the hole, but for the last few metres diesel fuel was used to balance the pressure of the seawater and circulate the cuttings. Near the bottom seawater began to leak into the hole. The final open hole depth was only 221 m because ice cuttings from reaming the hole feel to the bottom and formed a slush plug which could not be cleared before the end of the season.[81]

Setting ablation stakes might require hundreds of holes to be drilled; and if short stakes are used, the holes may have to be periodically redrilled. In the 1950s percussion drilling was still used for some projects; a mass-balance study on the Hintereisferner in 1952 and 1953 began with a chisel drill to drill the stake holes, but obtained a toothed drill from the University of Munich geophysics staff which enabled them to drill 1.5 m in 10 to 15 minutes.[82]

In the summers of 1958 and 1959, the Institute of Geography of the Кеңес Ғылым академиясы (IGAS) sent an expedition to Франц Йозеф жері in the Russian Arctic. Drilling was done with a conventional rotary rig, using air circulation. Several holes were drilled, from 20–82 m deep, in the Churlyenis ice cap; cores were recovered in runs of 1 m to 1.5 m, but they were usually broken into lengths of 0.2 m to 0.8 m. Several times the drill became stuck when condensation from the air circulation froze on the borehole walls. The drill was freed by tipping 3–5 kg of table salt down the hole and waiting; the drill came free in 2–10 hrs.[83]

Hot water drills

In 1955 Électricité de France returned to the Mer de Glace to do additional surveying, this time using lances that could spray hot water. Multiple holes were drilling to the base of the glacier; the lances were also used to clear entire tunnels under the ice, with the equipment adapted to spray the hot water through seventeen nozzles simultaneously.[84]

Development of electrothermal drills

A team from Cambridge University excavated a tunnel under the Odinsbre ice fall in Norway in 1955, intending to lay a 128 m pipe along the tunnel, with the intention of using inclinometer readings from within the pipe to determine details of the icefall motion over time.[85] The pipe was delivered late, and was not in time to be used in the tunnel, which closed unexpectedly quickly,[85][86] so in 1956 a thermal drill was used to drill a hole for the pipe. The drill had a 5 in diameter head, with the meltwater flowing to the outside of the drillhead rather than being drained through a hole. The drillhead was cone-shaped, which maximized the time the meltwater spent flowing over the ice, thus increasing the heat transfer to the ice. It also increased the metal surface for heat transfer. Since electrothermal drills were known to be at risk of fusing when they encountered dirt or rocky material, a thermostat was incorporated into the design. The sheath of the drill head was separable, in order to make it quicker to replace the heating element if necessary. Both the sheath and the heating element were cast into aluminium; copper was considered, but eliminated from consideration because the copper oxide film which would be quickly formed once the drill was in use would significantly reduce heat transfer efficiency.[87] In the laboratory the drill performed at 93% efficiency, but in the field it was found that the pipe joints were not waterproof; water seeping into the pipe was continuously boiled by the heater, and the rate of penetration was halved. The drill was set up on a slope of the ice fall that was at 24° from horizontal; the borehole was perpendicular to the ice surface. The penetration rate periodically slowed for a while but could be recovered by moving the pipe up and down or rotating it; it was speculated that debris in the ice would reduce the rate of penetration, and pipe movement encouraged the debris to flow away from the drill head face. Bedrock was reached at a depth of 129 ft; it was assumed to be bedrock once 14 hours of drilling led to no additional progress in the borehole. As with the tunnel, subsequent expeditions were not able to find the hole; it was later discovered that the nature of the icefall was such that ice in that part of the icefall becomes buried by additional ice falling from above.[88]

A large copper deposit under the Лосось мұздығы, in Alaska, led a mining company, Granduc Mines, to drill exploratory holes in 1956. W.H. Mathews, of the University of British Columbia, persuaded the company to allow the holes to be cased so they could be surveyed. A thermal drill was used since the drill site could only be accessed in winter and spring, and water would not have been easily available. A total of six holes were drilled; one, at 323 m, failed to reach bedrock, but the others, from 495 m to 756 m, all penetrated the glacier. The hotpoint was allowed to rest at the bottom of the hole for an hour at a time with slack in the cable; each hour the remaining slack would be pulled up and the progress measured. This led to a hole too crooked to continue, and subsequently a 20 ft length of pipe was attached to the hotpoint, which kept the borehole much straighter, although it was still found that the borehole tended to stray further and further away from the vertical once it began to deviate. The 495 m hole was the one cased with the aluminum pipe. Inclinometer measurements were taken in May and August 1956; a visit to the glacier in the summer of 1957 found that the pipe had become plugged with ice, and no further readings could be taken.[89]

Between 1957 and 1962 six holes were bored in the Blue Glacier by Ronald Shreve and R.P. Sharp from Caltech, using an electro-thermal drill design. The drill head was attached to the bottom of aluminium pipe, and when drilling was completed the cable down the pipe was broken at a low strength joint, leaving the drill at the bottom of the hole, resulting in a hole cased with the pipe. The pipes were surveyed with an inclinometer both when drilled and in following years. The pipes were frequently found to be plugged with ice when surveyed, so a small hotpoint was designed that could be lowered inside the pipe to thaw the ice so that inclinometer readings could be taken.[90] Kamb and Shreve subsequently drilled additional holes in Blue Glacier for tracking vertical deformation, suspending a steel cable in the hole instead of casing it with pipe. In following years, in order to take inclinometer readings, they redrilled the hole with a thermal drill design that followed the cable. This approach allowed finer resolution of the details of the deformation than was possible with a pipe.[91]

In the early 1950s Henri Bader, then at the Миннесота университеті, became interested in the possibility of using thermal drilling to obtain cores from holes thousands of metres deep. Lyle Hansen advised him that high voltage would be needed to prevent power loss, and this meant a transformer would need to be designed for the drill, and Bader hired an electrical engineer to develop the design. It lay unused until in 1958, with both Bader and Hansen working at SIPRE, Bader obtained an NSF grant to develop a thermal coring drill.[92][93] Fred Pollack was hired as a consultant to work on the project, and Herb Ueda, who joined SIPRE in late 1958, joined Pollack's team.[92] The original transformer design was used in the new drill,[93] which included a 10 ft long core barrel, weighed 900 lbs, and was 30 ft long.[94] It was tested from July to September 1959 in Greenland, at Туто лагері, жақын Туле әуе базасы, but only drilled a total of 89 inches in three months. Pollack left when the team returned from Greenland, and Ueda took over as the team lead.[92]

In 1958 the Cambridge team which had placed a pipe in the Odinsbre icefall in 1956 returned to Norway, this time to place a pipe in the Austerdalsbre мұздық. A defect of the Odinsbre drill was the wasted heat spent on water that collected in the pipe; it was thought impracticable to prevent water from entering the pipe, so the new design included an airtight chamber behind the heating element to separate it from any water that might collect. As before, a thermostat was included. The drill operated entirely successfully, with an average rate of penetration just under 6 m/hr. When the hole reached 397 m, drilling stopped, since this was the length of the available pipe, although bedrock had not been reached.[95] The following summer two more holes were drilled on the Austerdalsbre, using drills adapted from the previous year. The new drill heads were 3.2 inches and 3.38 inches in diameter, and the designs were similar: a sheath allowed easier replacement of the element, and a thermostat was included. 32.5 ft of aluminium tube was attached behind the drill head, with metal discs of 3.2 inches diameter screwed on at the midpoint and upper end. This succeeded in keeping the borehole straight. The 3.2 in drill was used to a depth of 460 ft, at which point water leakage damaged the drill head. The 3.38 in drill took the hole to 516 ft, but progress became extremely slow, probably because of debris in the ice, and the hole was abandoned. A second hole was started with the 3.38 in drill and this successfully reached bedrock at 327 ft, but the thermostat failed, and after some difficulty the drill was removed from the hole to find that the aluminium casting had melted, and the lower part of the drill head remained in the hole.[96]

A Canadian expedition to the Athabaska Glacier in the Canadian Rockies in the summer of 1959 tested three thermal drills. The design was based on R.L. Shreve's drill design, and used a commercial heating element originally intended for electric cookers. Three of these hotpoints were acquired; two were cut to 19-ohm lengths, and one to a 16-ohm length. They were wound into helices, and cast in copper, before being assembled into a form that could be used for drilling. The drill was made from pipe with an outside diameter of 2 in, and was 48 in long. The maximum design temperature for the heater's steel sheath was 1,500 °F; since it was determined that the normal operating temperature would be well below this, power was increased to over 36 watts per inch.[97]

The 16-ohm drill burned out at 60 ft depth; it was found to have overheated. One of the 19-ohm drills failed at one of the soldered junctions of the drill with the cable leading to the surface. The other drilled two holes, to 650 ft and 1024 ft, reaching a maximum drilling rate of 11.6 m/hr. The efficiency of the drill was about 87% (with 100% efficiency defined as the rate obtained when all the power goes into melting the ice). In addition, two other hotpoint drills were assembled in the field, to a different design. A total of five holes were drilled; the other two holes reached 250 ft and 750 ft.[98]

1960 жж

The Federal snow sampler was refined in the early 1960s by C. Rosen, who designed a version which consistently produced more accurate estimates of snow density than the Federal sampler. Larger-diameter samplers produce more precise results, and samplers with inner diameters of 65 to 70 mm have been found to be free of the over-measurement problems of the narrower samplers, though they are not practical for samples over about 1.5 m.[39]

A European collaboration between the Italian Comitato Nazionale per l'Energia Nucleare, Еуропалық атом энергиясы қоғамдастығы, және Centre National de Recherches Polaires de Belgique sent an expedition to Рагнильд жағалауы ханшайымы, in Antarctica in 1961, using a rotary rig with air circulation. The equipment performed well in tests on the Glacier du Géant in the Alps in October 1960, but when drilling began in Antarctica in January 1961, progress was slow and the cores recovered were broken and partly melted. After five days the hole had only reached 17 m. The difficulties appear to have been caused by the loss of air circulation into the firn layer. A new hole was begun, using the SIPRE auger as the drillhead; this worked much better, and in four days a depth of 44 m was reached with almost complete core recovery. Casing was set to 43 m, and drilling continued with air circulation, with a toothed drill, and ridges welded to the sides of the core barrel to increase the space around the barrel for air circulation. Drilling was successful to 79 m, and then the cores became heavily fractured. The core barrel became stuck at 116 m and was abandoned, ending drilling for the season.[83]

Edward LaChapelle of the University of Washington began a drilling program on the Көк мұздық in 1960. A thermal drill was developed using a silicon carbide heating element; it was tested in 1961, and used in 1962 to drill twenty holes on the Blue Glacier. Six were abandoned when the borehole encountered cavities in the ice, and five were abandoned because of technical difficulties; in three cases the drill was lost. The remaining holes were continued until non-ice material was reached, in most cases this was presumed to be bedrock, though in some cases the drill may have been stopped by debris in the ice. The silicon carbide element (taken from a standard electric furnace heater) was in direct contact with the water. The drill was constructed to allow rapid heating element replacement in the field, which proved to be necessary as the heating elements deteriorated quickly at the negative terminal when running under water; typically only 5–8 m could be drilled before the element had to be replaced. Drilling speed was 5.5 to 6 m/hr. The deepest hole drilled was 142 m.[99]

Another thermal drill was used in 1962 on the Көк мұздық, this time able to take cores, designed by a team from Cal Tech and the University of California. The design goal was to enable glaciologists to obtain cores from deeper holes than could be drilled with augers such as the one designed by SIPRE, with equipment sufficiently portable to be practical in the field. A thermal drill was considered simpler than an electromechanical drill, and made it easier to record the orientation of the cores; thermal drills were also known to perform well in water-saturated temperate ice. The drill reached the bed of the glacier in September 1962 at a depth of 137 m at a rate of about 1.2 m/hr; it obtained a total of sixteen cores, and was used in alternation with a non-coring thermal drill which was able to drill 8 m/hr.[100]

The first percussion drilling rig designed specifically for ice drilling was tested in 1963 in the Кавказ таулары бойынша Soviet Institute of Geography. The rig used a hammer to drive a tube into the ice, typically gaining a few centimetres with each blow. The deepest hole achieved was 40 m. A modified rig was tested in 1966 on the Karabatkak Glacier, жылы Terskei Alatau сол кезде болған Қырғыз КСР, and a 49 m hole was drilled. Another cable-tool percussion rig was tested that year in the Caucasus, on the Bezengi Glacier, with one hole reaching 150 m. In 1969, a US cable tool using both percussion and electrothermal drilling was used on the Көк мұздық Вашингтонда; the thermal bit was used until it became ineffective, and then percussion was tried, though it was found to be only marginally effective, particularly in ice near the base of the glacier, which included rocky debris. In Greenland in 1966 and 1967 attempts were made to use rotary-percussion drilling to drill in ice, both vertically and horizontally, but again the results were disappointing, with slow penetration, particularly in the vertical holes.[101]

A rotary drilling rig, using seawater as the circulating fluid, was tested at МакМурдо станциясы in the Antarctic in 1967, with both an open face bit and a coring bit. Both bits performed well, and the seawater was effective at removing the cuttings.[102] The drill tests were conducted by the US Navy Civil Engineering Laboratory, and were intended to establish suitable methods for construction work in polar regions.[103]

Steam drills

A study of the Hintereisferner in the early 1960s required placing stakes in hand-drilled holes to measure ice loss. Since up to 7 m per year of ice could be lost, the holes sometimes had to be redrilled partway through the year. To avoid this, a hand-operated steam drill was developed by F. Howorka. Two hoses were used, one inside the other, to reduce heat loss, and a 2 m long guide tube was attached to the inner hose at the end, in order to keep the borehole straight. A brass rod was used as the drill tip; the inner hose ran through the tube and rod and a nozzle was attached at the end of the rod. The drill was able to drill an 8 m hole in 30 minutes; one butane cartridge lasted about 110 minutes, allowing three holes to be drilled.[104]

A hand-held steam drill for placing ablation stakes was designed by Steven Hodge at the end of the 1960s. A Norwegian steam drill based on Howorka's 1965 design had been obtained by the Glacier Project Office of the Water Resources Division of the АҚШ-тың геологиялық қызметі to plant stakes on the South Cascades Glacier Вашингтонда; Hodge borrowed the drill to install ablation stakes on the Nisqually Glacier, but found that it was too fragile, and also too unwieldy to be brought to the glacier by backpack.[105] Hodge's design used propane, and took the form of an aluminium box, with the propane tank at the bottom and the boiler above it. An chimney could be extended from the drill to improve ventilation, and a side opening vented the burner gases. As with Howorka's design, an inner and outer hose were used for insulation purposes. Tests revealed that a simple forward hole in the nozzle did not give the most efficient results; additional holes were made in the nozzle to spread the spray evenly across the surface of the ice.[106] Two copies of the drill were built; one was used on the South Cascades Glacier in 1969 and 1970 and on the Gulkana and Wolverine Glaciers in Alaska in 1970; the other was used by Hodge on the Nisqually Glacier in 1969, on sea ice at Barrow, Alaska in 1970, and on the Blue Glacier in 1970. Typical drilling rates were 0.55 m/min, with a drill diameter of 1 inch. A 2-inch-diameter nozzle was tested; it drilled at 0.15 m/min. It was effective in ice with sand and rock inclusions. In Arctic conditions, with air temperatures below −35 °C, it was found that the steam would cool to water and form an ice plug before reaching the drill tip, but this could be avoided by running the drill indoors to warm up the equipment first.[107]

SIPRE and CRREL thermal drilling

In 1961 ACFEL and SIPRE were combined to form a new organization, the Салқын аймақтардың ғылыми-зерттеу зертханасы (CRREL).[108] Some minor modifications were subsequently made to the SIPRE auger by CRREL staff, so the auger was also sometimes known as the CRREL auger.[73]

The SIPRE thermal drilling project returned to Camp Tuto in 1960, achieving about 40 ft of penetration with the revised drill. The project moved to Camp Century from August to December 1960, returning in 1961, when they managed to reach over 535 feet, at which point the drill became stuck. In 1962 unsuccessful attempts were made to retrieve the drill, so a new hole was begun, which reached 750 feet. The hole was abandoned when part of the drill was lost. In 1963 the thermal drill reached about 800 feet, and the hole was extended to 1755 ft in 1964.[109] To prevent hole closure, a mixture of diesel fuel and trichloroethylene was used as a drilling fluid.[94]

Continual problems with the thermal drill forced CRREL to abandon it in favour of an electromechanical drill below 1755 ft. It was difficult to remove the meltwater from the hole, and this in turn reduced the heat transfer from the annular heating element. There were problems with breakage of the electrical conductors in the armoured suspension cable, and with leaks in the hydraulic winch system. The drilling fluid caused the most serious difficulty: it was a strong solvent, and removed a rust inhibiting compound used on the cable. The residue of this compound settled to the bottom of the hole, impeding melting, and clogged the pump that removed the meltwater.[94]

To continue drilling at Camp Century, CRREL used a cable-suspended electromechanical drill. The first drill of this type had been designed for mineral drilling by Armais Arutunoff; it was tested in 1947 in Oklahoma, but did not perform well.[110][111] CRREL bought a reconditioned unit from Arutunoff in 1963 for $10,000,.[110][111][112] and brought it to the CRREL offices in Hanover, New Hampshire.[110][111] It was modified for drilling in ice, and taken to Camp Century for the 1964 season.[110][111] The drill didn't need an antitorque device; the armoured cable was formed of two cables each twisted in opposite directions, so if the cable began to twist it provided its own antitorque.[113] To remove the cuttings, ethylene glycol was added to the hole with each trip; this dissolved the ice chips and the bailer, with diluted ethylene glycol, was emptied on each return to the surface.[114][115] Drilling continued for the next two years, and in June 1966 the EM drill extended the hole to the bottom of the icecap at 1387 m, drilling through a silty band at 1370 m depth, and then extending the hole below the ice to 1391 m. The subglacial material included a mixture of rocks and frozen till, and was about 50–60% ice. Inclinometer measurements were taken, and when the hole was excavated and reopened in 1988, new inclinometer measurements enabled the speed of the ice flow at different depths to be determined. The bottom 229 m of the ice, dating from the Висконсин мұздануы, was found to be moving five times as fast as the ice above it, indicating that the older ice was much softer than the ice above.[113]

In 1963, CRREL built a shallow thermal coring drill for the Canadian Department of Mines and Technical Surveys. The drill was used by W.S.B. Патерсон to drill on the ice cap on Мейген аралы in 1965, and Paterson's feedback led to two revised versions of the drill built in 1966 for the Австралия ұлттық антарктикалық зерттеу экспедициясы (ANARE) and the US Antarctic Research Program. The drill was designed to be used in both temperate glaciers and colder polar regions; drilling rates in temperate ice were as high as 2.3 m/hr, down to 1.9 m/hr in ice at 28 °C. The drill was able to obtain a 1.5 m core in a single run, with a chamber above the core barrel to hold the melt water produced by the drill.[116] In the 1967–1968 Antarctic drilling season, CRREL drilled five holes with this design; four to a depth of 57 m, and one to 335 m. The cores were shattered between 100 m and 130 m, and of poor quality below that, with numerous horizontal fractures spaced about 1 cm apart.[116][117]

A difficulty with cable-suspended drilling is that since the drill must rest on the bottom of the borehole with some weight for the drilling method—thermal or mechanical—to be effective, there is a tendency for the drill to lean to one side, leading to a hole that deviates from the vertical. Two solutions to this problem were proposed in the mid-1960s by Haldor Aamot of CRREL. One approach, conceived in 1964, was based on the idea that a pendulum will natural return to a vertical position, because the centre of gravity is below the point at which it is supported. The design has a hot point at the bottom of the drill with a given diameter; higher up the drill, at a point above the centre of gravity, there is a hotpoint built as an annular ring around the body of the drill. In operation the upper hotpoint, being wider than the lower one, rests on the edge of the borehole formed by the lower hotpoint, and gradually melts it. The relative power supplied to the two hotpoints controls the ratio of weight resting at each point. A test version of the drill was built at CRREL with a 4 in diameter, and was found to quickly return the borehole to vertical when started in a deliberate inclined hole.[118] Aamot also developed a drill that resolved the problem by taking advantage of the fact that thermal drills operate immersed in the water that they melt. He added a long section above the hotpoint that was buoyant in wanter, providing a force towards the vertical whenever the drill was fully immersed. Five of these drills were built and tested in the field in August 1967; hole depths ranged from 10 m to 62 m. All the drills were lost to hole closure, since the ice was thought to be a few degrees below zero; the use of an antifreeze additive to the borehole was considered but not tried.[119]

A third approach to the issue was suggested by Karl Philberth for use in thermal probes, which penetrate ice as a thermal drill does, paying out a cable behind them, but which allow the ice to freeze behind them, since the goal is to place a probe deep in the ice without expecting to retrieve it. For probes intended for very cold ice, the side walls of the probe are also heated, to prevent the probe from freezing in place, and in these cases additional vertical stabilization is needed. Philberth suggested using a horizontal layer of mercury just above the hot point; if the probe tilted away from the vertical, the mercury would flow to the lowest side of the drill, providing heat transfer from the hotpoint only to that side, and speeding up the heating on that side, which would tend to reverse the tilt of the borehole. The approach was successfully tested in the laboratory for short runs of the probes.[120][121]

In December 1967, drilling began at Берд станциясы Антарктидада; as at Camp Century, the hole was begun with the CRREL thermal drill, but as soon as the casing was set, at 88 m, the electromechanical drill took over. The hole was extended to 227 m in the 1967–1968 drilling season. The team returned to the ice in October, and the drill was operated round-the-clock, reaching a depth of 770 m by 30 November. After the hole reached 330 m, it showed a persistent and increasing deviation from the vertical, which the team were unable to reverse. By the end of 1968 the hole was at 11° from the vertical. Drilling continued to the bottom of the icecap, which was reached at the end of January at 2164 m, at which point the inclination was 15°. Cores were recovered from the whole length of the borehole, and were of good quality, although cores from between 400 m and 900 m was brittle. It was found impossible to get a sample of the material below the ice; repeated attempts were eventually abandoned for fear of losing the drill. The following season further attempts were made, but the drill became stuck and the wireline had to be severed, abandoning the drill. Inclinometer measurements in the hole over the next 20 years revealed that there was more deformation in the ice below 1200 m depth, corresponding to the Wisconsin glaciation, than above that point.[122][123]

1970 жж

JARE projects

Japan began sending research expeditions to the Antarctic in 1956; the overall research program, Жапондық Антарктикалық зерттеу экспедициясы (JARE) named each year's expedition with a numeral starting with JARE 1.[124] Drilling projects were not included in any of the expeditions until over a decade later, partly because Japan had no research station in Antarctica.[125] In May 1965 a group of glaciologists proposed a program for the expeditions from 1968 through 1972 that included some drilling; but because of resource constraints JARE decided to defer the drilling program to 1971, with JARE 11 establishing a depot at Mizuho in 1970.[126] In preparation two drills were designed and built.[125] JARE 140, designed by Yosio Suzuki, was based on blueprints of the CRREL thermal drill, though difficulties with obtaining materials led to multiple changes in the design.[125][127] The other, designed by T. Kimura, the head of the JARE 12 drilling team, was the first electromechanical auger drill ever built.[128][129][130] JARE XI set up a depot at Мизухо in July 1970, and in October 1971 JARE XII began drilling with the new electrodrill.[125] It proved to have many problems; the auger fins did not effectively move the chips upward to the upper half of the core barrel where they were to be stored, and as there was no outer barrel surrounding the auger, the chips frequently clogged the space between the drill and the borehole wall, overloading the motor, sometimes after only 20 or 30 cm of progress. The drill was also somewhat underpowered at 100 W. It became stuck at 39 m depth, and attempts to retrieve it led to the loss of the drill when the cable detached from the clamp on the drill. The thermal drill, JARE 140, was used to drill 71 m that November, but was also lost in the hole.[125][129] The following year, JARE XIII took a thermal drill, JARE 140 Mk II; plans for taking a new electrodrill had to be given up as it had proved impossible to find a suitable gear reduction mechanism to address the power issue.[130] The 140 Mk II reached 105 m on 14 September 1972, and then stuck; it was freed by pouring 60 litres of antifreeze in the hole. The pump was damaged; it was replaced and drilling was restarted in November, reaching 148 m by November 14, at which point the drill stuck once again and was abandoned. The problems with these drills, caused partly by the low temperatures of the season, led the JARE planners to decide to drill later in the austral summer, and do additional field testing before drilling in Antarctica again.[125]

An Icelandic team drilling for cores on Ватнайджулл glacier in 1968 and 1969, using a thermal drill, found they were unable to penetrate below 108 m, probably because of a thick ash layer in the glacier. They were also concerned about the possibility of meltwater from the thermal corer contaminating the isotopic ratio of the core they retrieved at shallower depths. They designed two drills to address these concerns. One was the SIPRE coring auger, with an electrical motor attached at the top of the hole; this extended the depth the auger was effective at from 5 m to 20 m. The other new design was a simplification of the CRREL cable-suspended drill. It had helical flights to carry the ice chips to a storage compartment above the core barrel, and was designed to run submerged in water, since the previous years' experience had found water in the hole from 34 m. The drill was used in the summer of 1972 on Vatnajökull glacier, and penetrated the ash layers without difficulty, but problems were encountered with the drill sticking at the end of the run, probably because of ice chips freezing in the gap between the hole wall and the drill barrel. The drill was freed by applying tension to the cable in these cases, and to limit the problem each run was begun with a bag of isopropyl alcohol tied inside the core; the bag burst when drilling began, and the alcohol, mixing with water in the hole, acted as an antifreeze. Drilling stopped at 298 m when the cable became damaged; a new cable, 425 m long, was obtained from CRREL, but this only allowed the hole to reach 415 m, which was not deep enough to reach the bed of the glacier.[131][132][133]

JARE returned to the field in 1973 with a new electromechanical auger drill (Type 300) built by Yosio Suzuki, of Хоккайдо университеті Келіңіздер Institute of Low Temperature Science, and a thermal drill (JARE 160). Since Nagoya University was planning to obtain ice cores on ice island Т-3, the drills were tested there, in September, and obtained multiple cores with 250 mm diameter using the thermal drill. The electrodrill was modified to address issues found during test drilling, and two revised versions of the thermal drill (JARE 160A and 160B) were built as well, for use in the 1974–1975 Antarctic drilling season.[134]

In 1977 JARE approached Yosio Suzuki, who had been involved with JARE drilling in the early 1970s, and asked him to design a method of placing 1.5m3 of dynamite below 50 m in the Antarctic ice sheet, in order to perform some seismic surveys. Suzuki designed two drills, ID-140 and ID-140A, to drill holes with 140 mm diameter, intended to reach 150 m in depth. The most unusual feature of these drills was their anti-torque mechanism, which consisted of a spiral gear system that transferred rotary motion to small cutting bits that cut vertical grooves in the borehole wall. Fins in the drill above these side cutters fit into the grooves, preventing rotation of the drill. The only difference between the two models was the direction of rotation of the side cutters: in ID-140 the cutting edge of the bits cut upwards into the borehole wall; in ID-140A the edge cut downwards.[135][136] Testing these drills in a cold laboratory in late 1978 revealed that the outer barrel was not perfectly straight; the deviation was large enough to make it impossible to drill without a heavy load. The jacket was replaced with a machined steel jacket, but further testing made it clear that the auger was ineffective at transporting the chips upwards. A third jacket, rolled from a thin steel sheet, was made, and the drill was sent to Antarctica with JARE XX for the 1978–1979 drilling season; this jacket was too weak and was crushed in the first drilling run, so the second jacket had to be used. Despite the poor cuttings clearance, a 63 m deep hole was drilled, but at that depth the drill became stuck in the hole when the anti-torque fins lost alignment with the grooves cut for them.[137][138] In 1979 Kazuyuko Shiraishi was appointed to lead the JARE 21 drilling program, and worked with Suzuki to build and test a new drill, ILTS-140, to try to improve the chip transportation. The barrel for the test drill was made of a pipe formed from a sheet of steel, and this immediately solved the problem: the seam formed by the joining of the sheet's edges acted as a rib to drive the cuttings up the auger flights. In retrospect it was apparent to Suzuki and Shiraishi that the third jacket built for ID-140 would have solved the problem had it been strong enough, as it also had a lengthwise seam.[137][138]

Shallow drill development

In 1970, in response to a perceived need for new equipment for shallow and intermediate core drilling, three development projects were begun at CRREL, the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Bern. The resulting drills became known as the Rand drill, the Rufli drill, and the University of Copenhagen (or UCPH) drill.[112][139] The Rand and Rufli drills became the model for further development of shallow drills, and drills based on their design are sometimes referred to as Rufli-Rand drills.[128]

In the early 1970s a shallow auger drill was developed by John Rand of CRREL; it is sometimes known as the Rand drill. It was designed for coring in firn and ice up to 100 m, and was first tested in 1973 in Greenland, at Milcent, during the GISP summer field season. Testing led to revisions to the motor and anti-torque system, and in the 1974 GISP field season the revised drill was tested again at Crête, in Greenland. A 100 m core was obtained in good condition, and the drill was then shipped to Antarctica, where two more 100 m cores were obtained in November of that year, at the South Pole and then at J-9 on the Ross Ice Shelf. The cores from J-9 were of poorer quality, and only about half the core was recovered at J-9 below 75 m. The drill was used extensively in Antarctica over the next few years, until after the 1980–1981 austral summer season. After that date the PICO 4 in drill took over as the drill of choice for US projects.[140][141][142]

Another drill based on the SIPRE coring auger design was developed at the Physics Institute at the University of Bern in the 1970s; the drill has become known as the "Rufli drill", after its principal designer, Henri Rufli. As with the Icelandic drill, the goal was to build a powered drill capable of extending the SIPRE auger's range; the goal was to drill quickly to 50 m with a lightweight drill that could be quickly and easily transported to drillsites.[143][144] The core barrel in the final design resembled the SIPRE coring auger, but was 2 m longer; the combined weight of this section and the motor and antitorque sections above it was only 150 kg, with the heaviest single component weighing only 50 kg. It retrieved cores between 70 cm and 90 cm in length, with the ice chips captured by holes in the sides of the barrel above the core.[145] The system was initially tested in 1973, at Dye 2, in Greenland; the winch was not yet completed, and there were problems with the coring section, so the SIPRE auger was substituted for the duration of the test. A 24 m hole was drilled with this equipment. 1974 жылдың ақпанында өзек баррельдің жаңа нұсқасы қармен жүру арқылы Юнгфраучода сыналды, ал наурызда электр лебедкасынан басқа барлық компоненттер сыналды Плейн Морте, Альпіде. Сол жазда бұрғылау Гренландияға апарылып, Summit (19 м), Crête (23 м және 50 м) және Dye 2 (25 м және 45 м) ойықтарында бұрғыланды.[146][143]

Руфли бұрғысы сыналғаннан кейін көп ұзамай Берн университетінде тағы бір шнек бұрғысы салынды; UB-II бұрғысы Rufli бұрғылауымен салыстырғанда ауыр болды, жалпы салмағы 350 кг.[5 ескерту] Ол 1975 жылы Гренландияда төрт өзекті, Dye 3-те (ең терең шұңқыр, 94 м бұрғыланды), Оңтүстік күмбезде және Ханс Таусен мұз айдынында бұрғылау үшін қолданылған. 1976 және 1977 жылдары Альпідегі Колле Гнифеттиде тағы екі ядро қалпына келтірілді, ал келесі жылы бұрғылау Гренландияға оралды, III лагерьде 46 м және 92 м. Ол Альпіде, Вернагтфернерде, 1979 жылдың наурыз-сәуір айларында үш ұңғыма бұрғыланды, ең жоғарғы тереңдігі 83 м. Содан кейін бұрғылау Востоктағы кеңестік станцияға жеткізілді, ал PICO командасы 100 м және 102 м екі тесікті бұрғылады.[147]

The Ross мұз сөресі жобасы 1973 жылы басталған 1976 ж. қазан айынан бастап Сөреге төрт тесік бұрғылауға тырысқан 1976 ж. Олар овершотпен бірнеше рет проблемалар туындады (ядро оқпанын алу және ауыстыру үшін құрал сымға түсірілді); ол тесік түбіне түсірілмес бұрын кездейсоқ үш рет босатылды. Үшінші оқиғадан кейін команда CRREL термиялық бұрғысын пайдаланып, жаңа саңылауға ауыспас бұрын 147 м-ге дейін ұңғыманы бұрғылауға көшті. Бұл тесік жабылғанға дейін және бұрғылау орнын ұстап қалмас бұрын 330 м дейін бұрғыланды. Команда ашық тереңдікті осы тереңдікке дейін жабылмай бұрғылауға болады деп сенген, бірақ бұрғылау жоғалғаннан кейін мұздың қысымын теңестіру үшін шұңқырдағы сұйықтықпен болашақ әрекеттерді жасау керек деп шешті. 1977 ж. Қаңтарда бұрғылау маусымы аяқталғанға дейін 171 м дейін бұрғылау үшін тағы бір сымды бұрғылау жүйесі қолданылды. арктикалық дизель отыны араласқан трихлорэтилен тесік 100 м жеткенде.[148][149]

Копенгаген университетінде 1970 жылдардың соңында екі жаттығу жасалды. Біреуі таяз шнек бұрғысы болды, оған Данияның қатысуымен жасалған Гренландия мұзды қабаты жобасы (GISP). UCPH таяз бұрғысы деп аталатын бұл бұрғылаудың жалпы салмағы 300 кг болатын, оны бір шанаға салуға болатын. Мұны жалғыз адам басқара алады, ал басқа адам өзегіне кіріп, өзегін орайды. Ол алғаш рет 1976 жылы мамырда Гренландиядағы Dye 3-те, содан кейін бұрғылау жоғалған Ганс Таузен мұз айдынында сыналды. Жаңа нұсқасы 1977 жылғы маусымда салынды және ол максималды 110 м тереңдіктен 629 м ядро алынған тиімді дизайн болып шықты. 1977 ж. Бұрғылау маусымының аяғында 100 м шұңқырды 10 сағатта бұрғылауға болады. Негізгі сапасы өте жақсы болды. 110 м-де бұрғылау бірнеше сағат бойы тұрып, тесікке гликоль құю арқылы босатылды. Дизайн 1980 жылдары кейбір ұсақ мәселелерді шешу үшін өзгертілді, содан бері Гренландияда UCPH таяз бұрғысы жиі қолданылып, 1988 жылы 325 м тереңдікке жетті. Бұрғыны арнайы қондырғы бекітіліп, қайта ойнатуға да қолдануға болады. өзек оқпанының орнына жетек блогына.[150][151][152]

1970 жылдардағы басқа Копенгаген университетінің бұрғысы 1977 жылы жобаланып, «ISTUK» деп аталды, «is», дат сөзі мұз, ал «тук», Гренландия - бұрғылау.[153][154] Ұңғыма қозғалтқышы батарея жинағымен басқарылды, ал бұрғылауды жермен байланыстырған кабель шарлау кезінде батареяны зарядтай берді. Бұрғылау уақыты әдетте алты минутты құрайтындықтан, толық сапар бір сағатқа созылуы мүмкін болса, бұл кабель тек батареяның орташа қуат шығынын қамтамасыз етуі керек дегенді білдіреді және бұл өз кезегінде кабельдің өлшемдерін 10 есе азайтты: кабельдің диаметрі 6,4 мм болды және 3300 м тереңдікте қозғалтқышты қуаттай алатындай етіп жасалған. Бұрғылау басына үш кескіш пышақ кірді, олардың әрқайсысының үстінде каналы бар, және бұрғылау айналған кезде бұрғылау ішіне біртіндеп жоғары созылып, бұрғылау сұйықтығын сорып, мұз кесінділерін арналарға қоймаға дейін жеткізетін үш поршеньді қамтыды. Бұрғылаудың айналасында орналасқан үш негізгі ұстаушы болғанымен, олардың тек екеуін қолдану бұрғылау кезінде ядроны бұзуға тиімді болатындығы анықталды, себебі бұл асимметриялық кернеу тудырды. Бұрғыдағы микропроцессор батареяны, инклинометрді және басқа жабдықты бақылап, кабель арқылы жер бетіне сигнал жіберді.[155]